Afghan Refugees in Limbo as Germany Suspends Humanitarian Entry Programme

ISLAMABAD/BERLIN — July 4, 2025:

Thousands of Afghan refugees, including women’s rights activists and former journalists, remain stranded in Pakistan after Germany suspended its humanitarian admission programme intended for vulnerable Afghans fleeing Taliban rule.

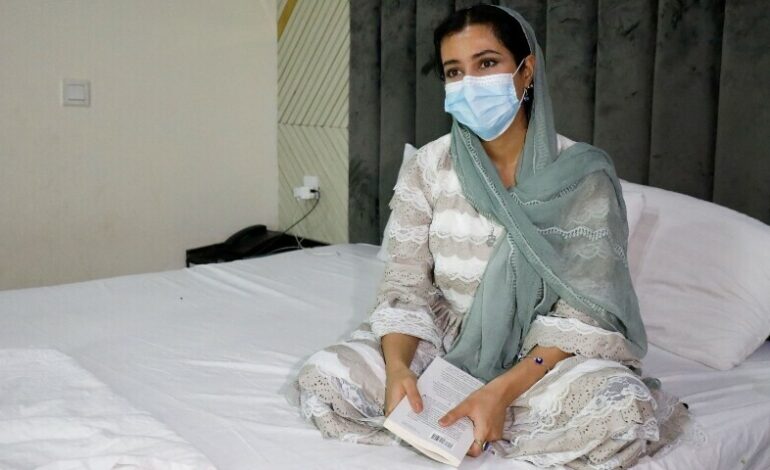

Among those affected is 25-year-old Kimia, a visual artist and advocate for women’s rights, who fled Afghanistan in 2024. Despite being approved for relocation under the German initiative, she now finds herself stuck in Islamabad after her final interview at the German Embassy was abruptly canceled in April.

“All my life comes down to this interview,” she said, requesting anonymity for security reasons. “We just want to find a place that is calm and safe.”

Germany Halts Programme Amid Political Shift

Launched in October 2022, Germany’s humanitarian admission programme aimed to resettle up to 1,000 at-risk Afghans per month, including those targeted for their gender, profession, or political beliefs. However, fewer than 1,600 have successfully arrived in Germany to date.

The situation worsened following Germany’s February 2025 elections, where migration dominated public discourse. The new centre-right coalition, led by Chancellor Friedrich Merz, has signaled its intent to permanently close the programme, citing “integration capacity” concerns.

“As long as we have irregular and illegal migration to Germany, we simply cannot implement voluntary admission programmes,” said Thorsten Frei, chief of staff to the chancellor.

Currently, an estimated 2,400 Afghans remain in limbo, having already cleared the vetting process, while 17,000 more applicants are at earlier stages of selection, according to German officials.

Legal Battles and Growing Anxiety

Several Afghans have filed legal challenges against the suspension. Matthias Lehnert, a Berlin-based lawyer representing the refugees, argues that Germany cannot cancel resettlement promises without legally valid grounds.

In interviews with Reuters, Afghan refugees expressed growing fear that public sentiment—swayed by recent violent incidents involving asylum seekers—is being unfairly projected onto them.

“I’m sorry for those victims, but it’s not our fault,” said Kimia, referencing an Afghan asylum seeker charged in a mass stabbing incident in Mannheim earlier this year. Approval rates for Afghan asylum applications have since dropped from 74% in 2024 to 52% in 2025, according to Germany’s Federal Migration Office (BAMF).

Lives on Hold in Pakistan

Women like Marina, a 25-year-old mother separated from her family, and Hasseina, a journalist facing threats from both the Taliban and her ex-husband’s family, are caught in a dangerous stalemate. Pakistan’s intensified deportation campaign against undocumented Afghans adds further urgency.

“If I go back, I can’t follow my dreams — I can’t work, I can’t study. It’s like you just breathe, but you don’t live,” said Kimia.

Germany continues to fund housing and basic needs for programme participants still in Pakistan. However, with no timeline provided for resuming resettlement, the affected refugees remain trapped in uncertainty.

Human rights advocates warn that delaying or scrapping the programme not only endangers lives but undermines Germany’s international commitments to protect vulnerable populations.